I was thinking recently that here in the West we take our video game history largely for granted. Look back at the Golden Age of video games, and it’s apparent that we had it pretty good – a regular supply of new titles that pushed the technological boundaries were pumped out from America’s arcade manufacturers during the late 70s and early 80s – and we are fortunate enough to be able to play most titles via cheap and plentiful emulation, or indeed for those of us who choose to, using the original hardware. Aesthetically, the early arcade machines came with a pleasing design, including mostly glorious artwork and stylish cabinets.

But what about other parts of the world? What did our far off neighbours have in their arcades, if anything at all? To try to get some insight, I recently spoke with Daria Zvereva the curator at The Museum of Soviet Arcade Games.

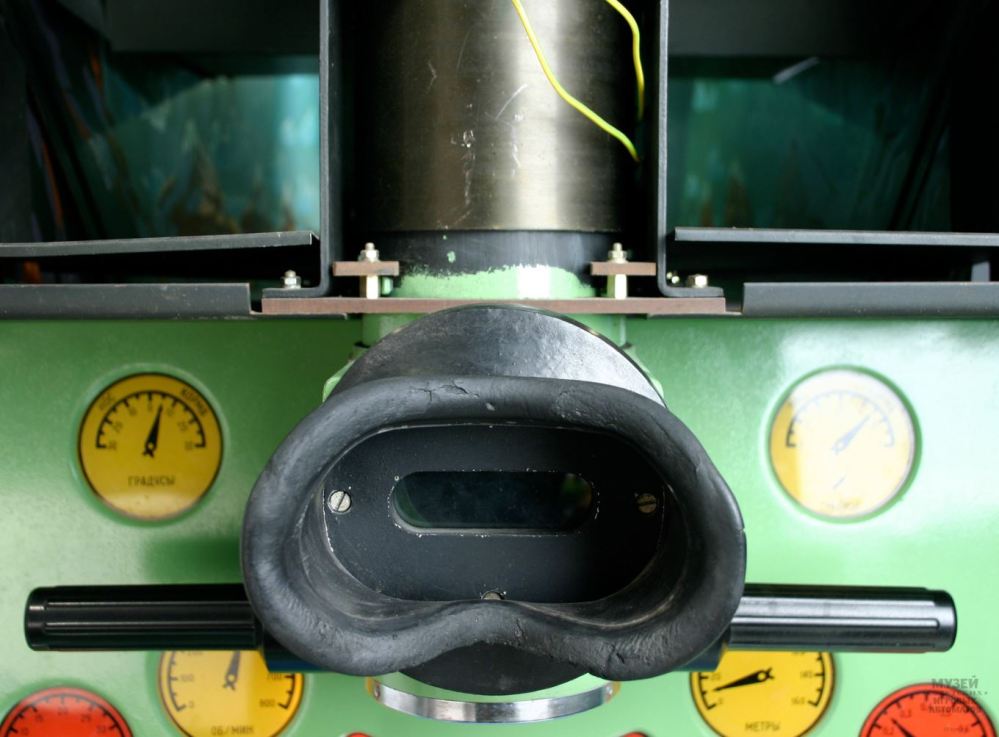

With two locations in both Moscow and St Petersburg (opened in 2007 and 2013 respectively), the museum plays host to an wide collection of original video game and electromechanical machines, which not only showcase the uniqueness of Russian engineering and industrial design, but also reflect Soviet ideology of the time – their themes intended to provide practical skills (driving, shooting and aiming), rather than what might be regarded as more trivial pursuits like shooting down exotic invaders from space or saving stranded princesses from the clutches of oversized gorillas.

Approximately 250 machines are held within the collection, with just over 100 exhibited out on the floors of both locations. The remainder are in storage, awaiting restoration.

After buying an entrance ticket each visitor gets a fistful of original Soviet 15 kopek coins to operate the arcade machines (one kopek being one hundredth of a Ruble). Tours are provided every hour (in English if required), giving an insight to the history of arcade culture in the USSR. Other artefacts can be found dotted around including Soviet vending machines (stocked with classic drinks!), an old analogue photo booth (imported from the West) and even a vintage ping-pong table.

I asked Daria how the museum started:

The Museum was founded by 3 friends who wanted to relive their childhood memories of playing these old Soviet arcade games once more. One of them recalled that when they were kids, there had been a very famous arcade machine called Morskoi Boy (“Sea Battle”). They started doing some research and it turned out that even in 2006 in Moscow there were a lot of these old machines lying around. Of course, the majority of them were out of service, because no one produced or serviced them any more. Starting with just three machines found in the old Amusement Park in Moscow, the collection has rapidly grown, into what it is today.

In making these games available to the public, it became evident that there was genuine interest, as many visitors recall them being a significant part of Russian culture:

We find that even our young visitors can make comparisons between Soviet arcades and modern games, and appreciate the first ones as tangible heritage. So, there are a lot of reasons so far why we have to preserve the Soviet arcades!

Whilst the vast majority of machines on display were built and released in the mid 1980’s, production of arcade machines in the USSR began in the early 1970’s. Several examples can be played: Sniper arcade dated 1976 resides in the Moscow property; Plane Rocker from 1977 is a kiddie ride, and the aforementioned Sea Battle arcade from 1978 in Saint Petersburg.

A playable version of Sea Battle is available to play here (requires Flash). It’s actually really good fun.

Perhaps most fascinating, was Darius’ explanation of how these machines came to be:

The main producers of Soviet arcade machines were military factories, because they had funds and the skills to produce them, usually using leftover parts from real weapons, electronics and redundant pieces of industrial equipment. The view of the Government at the time was that the machines were very expensive: the cost of one arcade machine nearly equalled the cost of half of a Soviet car. The State decided not to establish companies and factories specializing in the manufacture of arcade games. Therefore, mass production of arcade machines in the Soviet Union was never really established.

Given the sporadic production, it is very difficult to establish exactly who produced each machine, and where they might have been built. The Soviet military factories were classified and to this day there is little or no mention of their names or locations. Usually, a machine may adorn nothing more than a serial number and a factory logo. With so little to go on, and next to no supporting documentation, the museum team spends countless hours trying to establish a definite history of the inventory they have.

Approximately 90% of Soviet arcade machines were copies of western ones — shooters, foosball games, pinball, etc. One very popular Soviet Basketball arcade machine is a copy of Sega Basketball. And probably the most famous Soviet arcade game of all is called Sea Battle, which was a copy of Sea Devil, made by USA manufacturer Midway Inc.

Although it would be unfair to attribute all Russian arcade games of the times as bootlegs of their Western counterparts. “Homegrown” Russian arcade machines do exist, and many are on display at the museum. Here’s a couple of examples:

Arcade machines were quite widespread in the USSR, but not as much as in the West. There was a distinct lack of any “gaming culture” in the USSR, coupled with an overwhelming sense among Soviet citizens that arcade machines were something of a folly, and what little money was around should be spent on the practicalities of life under the Soviet regime rather than being squandered on playthings.

Finding these machines is always a challenge (at least this is something we share over here in the West!). As Daria explains:

The initial core of the Museum’s collection was formed at the beginning of the Museum’s history. At the end of 2000s, we would go on fact-finding trips to many towns and villages in Russia and even former Soviet republics. We would come across machines at the places where they were originally located during the Soviet era — in former pioneer camps, cinemas and abandoned amusement parks. Today the main information source regarding new locations is from our visitors. It is they who very often tell us about abandoned arcade machines they have seen somewhere.

But perhaps the biggest challenge facing Darius and his team is restoring and maintaining everything:

We try to restore the arcade machines by using original Soviet spare parts (which are usually obtained from other machines which could not be restored), that is why the restoration process and maintenance are quite problematic. Moreover, there are also other issues we struggle with, for example, the absence of technical documentation, which is essential, because many were bespoke built using individual designs. Also, the logical structure of electronic and electromechanical parts found in Soviet arcade machines is very different from what we have today. Therefore, much of the equipment used is really hard to replace. Add to that, the lack of what I would call “vintage technical expertise” doesn’t help!

What I find interesting, is the distinct industrial design of these machines. Each is very distinctive and very much of their origin. In the USSR gaming “industry” there were no designers as such – function was the order of the day – aesthetics took very much a back seat. The games were built at military factories, and very often the appearance of these machines was a result of engineering functionality perhaps with the help of graphic designers. The only guidance they would have had, would have been based on the surroundings in which they were manufactured. Of note is that fact that most machines are upright, floor-standing cabinets – a result of the requirement for the machines to be lined up against the walls of the factories in which they were built.

So what does the future hold for this fascinating place?

From its humble start in 2007, the Museum has been entirely self-funded. Getting it recognised as a true museum with state support is extremely difficult. International exhibitions are impossible without this state assistance, so to see these machines does require a trip to one of the two locations. But recognition by some of Russia’s larger museums is much simpler — our Museum has already become a significant point on the attraction maps of both cities, so we are planning to just keep going do the things we like and are able to do.

To give you an idea of what to expect when you visit, here’s a great video giving a walk around of the museum in St Petersburg:

More information about both museums, including opening times and access details are available here.

Many thanks to Daria for talking with me and sharing these great pictures. If you visit one of the museums, be sure to say hello. I plan to get there sometime soon!

Thanks for reading this week.

Tony