Most of us understand by now that we’re being followed across the web. But how much do we know about how the smartphone apps we use track our every move? Thanks to tiny pieces of code that millions of developers use to make their lives easier, an array of companies gets free access to data they can employ to understand your habits. The process is invisible, and it’s worse news for you than you might think.

Most of us understand by now that we’re being followed across the web. But how much do we know about how the smartphone apps we use track our every move? Thanks to tiny pieces of code that millions of developers use to make their lives easier, an array of companies gets free access to data they can employ to understand your habits. The process is invisible, and it’s worse news for you than you might think.

When we browse the web through Google Chrome, for example, a dizzying array of companies follow us. Such is the Wild West of our modern web, but you still remain in control of which sites you visit and which social networks you log into.

The shift to native apps changes this equation, however. Suddenly you’re no longer in full control of what’s loaded, nor of who is tracking you, and you must trust app developers to do the right thing.

All of this should make you skeptical of marketing like Apple’s recent “privacy matters” campaign.

On mobile, tracking is generally performed through the use of a “software development kit” or SDK—a set of tools that helps app developers get something done faster. Many SDKs help developers debug their code or hook into useful services, but others help advertisers and marketing companies peer into your private life. Take the iHeartRadio app for example: Last fall, Medium reported that it contained code from Cuebiq’s SDK, which would permit user data to be sold for the purposes of ad tracking.

All of this should make you skeptical of marketing like Apple’s recent “privacy matters” campaign. While the company offers tools within Safari to block trackers on the web, it doesn’t offer any control over trackers embedded in apps that are distributed through the iOS App Store. Most people use the Google Chrome browser anyway, and it has even fewer privacy protections baked in. (Apple does ask developers to “respect user preferences for how data is used,” but good luck with that.)

SDKs present a solution to Apple’s pesky tracking restriction for advertisers. They can connect who you are between apps, provided the developer of each app uses the same SDK and the advertiser is able to use signals to figure out who you are. If we look at the top 200 apps on the iOS App Store, it’s interesting to see how broad the reach of most SDKs actually is.

The top 10 most commonly used SDK libraries in the top iOS apps, as reported by analytics firm Mighty Signal, are largely provided by Facebook (three out of 10) and Google (four out of 10). Google’s AdMob tools, for example, helps developers show advertising and track their users, and it’s integrated into 78% of the top apps on iOS—everything from the Holy Bible to LinkedIn. Facebook’s “Core Kit,” which provides access to the social platform’s features, is integrated into 61% of top apps. The list goes on.

Both of these SDKs allow Facebook and Google to track users beyond their desktop web browsers and automatically collect information like when you installed the app, each time you opened it, and what you purchased.

Tracking in SDKs is clearly part of the modern App Store ecosystem, and it goes far beyond the big corporate names. There are a dizzying array of companies you’ve never heard of invisibly tracking your habits in apps you use every day. Networks like Vungle, Apps Flyer, and Applovin all call themselves “advertising and analytics” platforms. They help developers monetize their apps, and all of them track data to sell to other partners behind the scenes as well.

This often overflows into our daily lives in weird ways. The technology podcast Reply All recently dug into mysterious automated robocalls, which were somehow matching the area code of producer Damiano Marchetti, even adjusting to different locations as he traveled. How could such robocallers know where you physically are?

After digging into all of Damiano’s apps, Reply All made a discovery: He had downloaded a game called Mobile Legends: Bang Bang, which reported the phone’s location and IMEI (a unique identifier) to a bunch of analytics companies, which then sold that data, eventually leading to robocallers purchasing it.

The world of SDKs is intentionally obfuscated from view in the same way a magician wishes their most impressive tricks to remain secret.

The Wall Street Journal recently wrote about data collection on millions of other apps, such as those intended for menstrual cycle and body weight tracking. Those apps were found to sell this data to Facebook. Many people assume that Facebook is monitoring their microphones, but the reality is that they don’t need to: They can just collect data from the apps you’re using all day long.

In the past, Apple has moved to make it more difficult to identify you by blocking access to unique identifiers and your phone number, but it’s still trivial to correlate an identity via your IP address, the name of a Wi-Fi network, or just matching together the bread crumbs of data they grab about you. Android allows even broader access to identifiers—not surprising, given that it’s built by a company that relies on advertising to make money.

The world of SDKs and the companies tracking with them is intentionally obfuscated from view in the same way a magician wishes their most impressive tricks to remain secret. If you knew that the game you love was the one ratting out your habits, you’d probably consider uninstalling it.

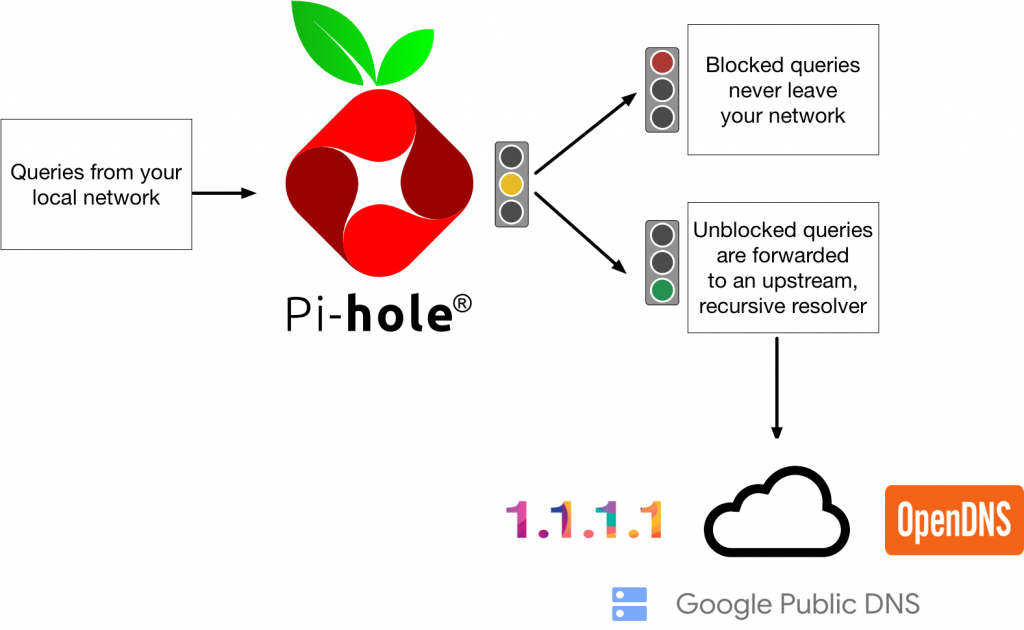

There’s frustratingly little we can do to combat SDK tracking without intervention from Apple and Google. There are nuclear methods that can help protect you, such as installing a network-wide ad-blocker on your home Wi-Fi, which blocks the requests at the source—but of course that only works within the confines of your home. On the go, some VPN providers are able to block advertising, but with the same limitations: You must stay connected to the VPN at all times to block them, which simply isn’t realistic.

What we really need is change from the top. Apple and Google should provide operating system controls that show the parties harvesting data inside the apps on our devices or should require third parties to reveal this information. A good example of this in practice can be found in the Guardian app, which allows users to disable tracking on a per-SDK basis in its settings. Requiring this should be standard for all developers.

Ultimately, the gatekeepers of mobile app stores have a responsibility to give us more control. Otherwise, the next big privacy scandal will be the digital equivalent of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: All our information out there, under the surface, helping companies build a picture of who we are—without us ever seeing it.