For more insight into developments in submarine connectivity in the APNIC region and worldwide, read our submarine cable series.

In 2018 we created around 2.5 million terabytes of data every day. This roughly equals 425 million HD movies a day. Any comparison is in itself massive, so it is understandable if these numbers are difficult to grasp. What’s more, data creation is growing at an exponential rate every year.

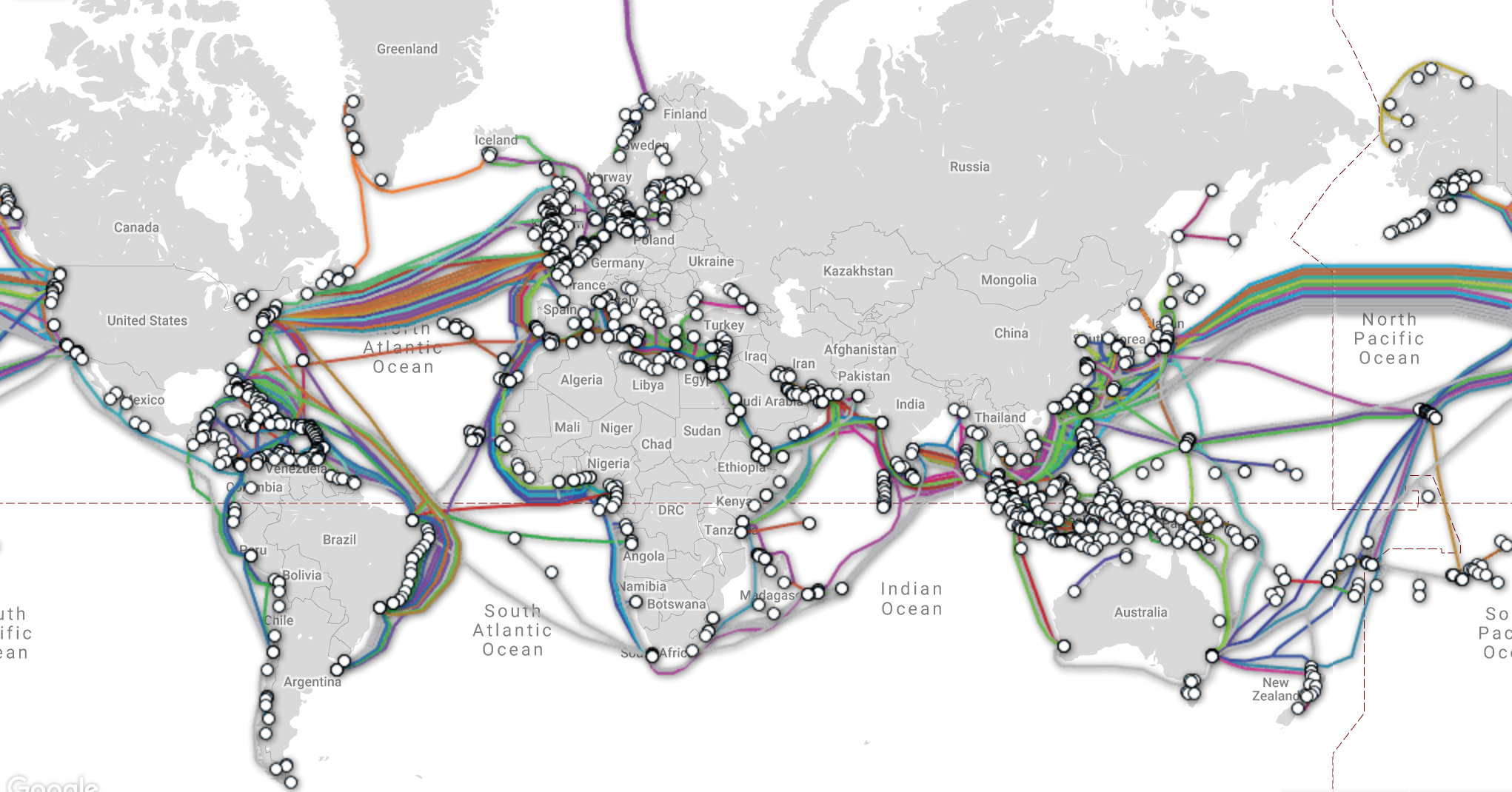

All this data exists in different storage centres across the world. But I am able to access the statistics shown here, probably stored in servers in the US, while sitting in India, because of the Internet — the greatest invention of the 20th and 21st centuries. But when we think of the Internet, many wrongly assume that satellites in space keep us connected with different parts of the world. In reality, 99% of the data travels between economies and continents through undersea cables.

Figure 1 — TeleGeography’s Submarine Cable Map (March 2019).

As of today, there are close to 400 active undersea cables, which are each no wider than a soda can in diameter. Laying these cables across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, some parts of which are as deep as Mount Everest is high, is a mammoth task. It takes years of route exploration, billions of dollars and large ships capable of holding cables that can be several thousand kilometres long. The main component of the cable, the optical fibre, is as thin as a hair. Each cable has a few optical fibre pairs that are covered with many layers of protection to prevent damage by boats, fishing activities and natural disasters. Despite the cost and difficulty of installing these cables, they are far cheaper and more efficient than satellites. Optical fibre has existed for a while now, but it is state-of-the-art technology, allowing data to travel at speeds close to that of light. The amount of data they can carry is also far more than what we can expect from satellites. An older cable can carry data equal to 1,500 HD movies per second. Satellites are still used in remote parts of the world, such as Antarctica for research purposes, where the data is strictly rationed and it is impossible to stream movies or download large files.

Between 2016 and 2020 about 100 new cables have been laid or planned. The primary reason for new cables is the demand for bandwidth. But it is difficult to pinpoint the source of this demand. An increase in Netflix viewing might seem like a good source because streaming movies stored in the US can use a lot of bandwidth, but this is not the case. Netflix usually sends a copy of a movie to a region once, where it is cached and stored locally. Similarly, the Internet of Things is a buzzword associated with large amounts of data, but even in 2020, it is expected to be only about one percent of global Internet traffic because much of the processing will happen locally. Demand can stem from unpredictable sources, such as the sudden increase in traffic when Pokemon Go was introduced. Despite the source, there is a consensus that bandwidth demand is doubling every two years, and hence new cables are required to keep up.

But bandwidth demand is not the only reason for new cables. To understand the other reasons, we first need to distinguish between a cable’s lit capacity vs potential capacity. Lit capacity is the amount of capacity a cable is currently equipped to handle. Potential capacity, on the other hand, is the theoretical maximum capacity that a cable can support if additional capital was invested to fully equip the cable system. In most major routes, the lit share of potential capacity is less than 30%. This would suggest that we can invest in existing cables and make use of the remaining unlit capacity, but this is generally not the case.

Companies prefer laying out newer cables because they are far more technologically advanced. The unit cost is cheaper for new cables than old cables whose lit capacity is increased. In other words, new cables have better economies of scale. The second reason is that old cables have few or no spare fibre pairs. While companies can make use of the unlit capacity by sharing existing fibre pairs, content providers like Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Amazon, given their large demand, prefer buying whole fibre pairs. Other reasons for new cables include connecting some remote parts of the world that are still reliant on satellites and providing more options to economies that have only one or two cables, because any damage to these cables can cause massive disruptions.

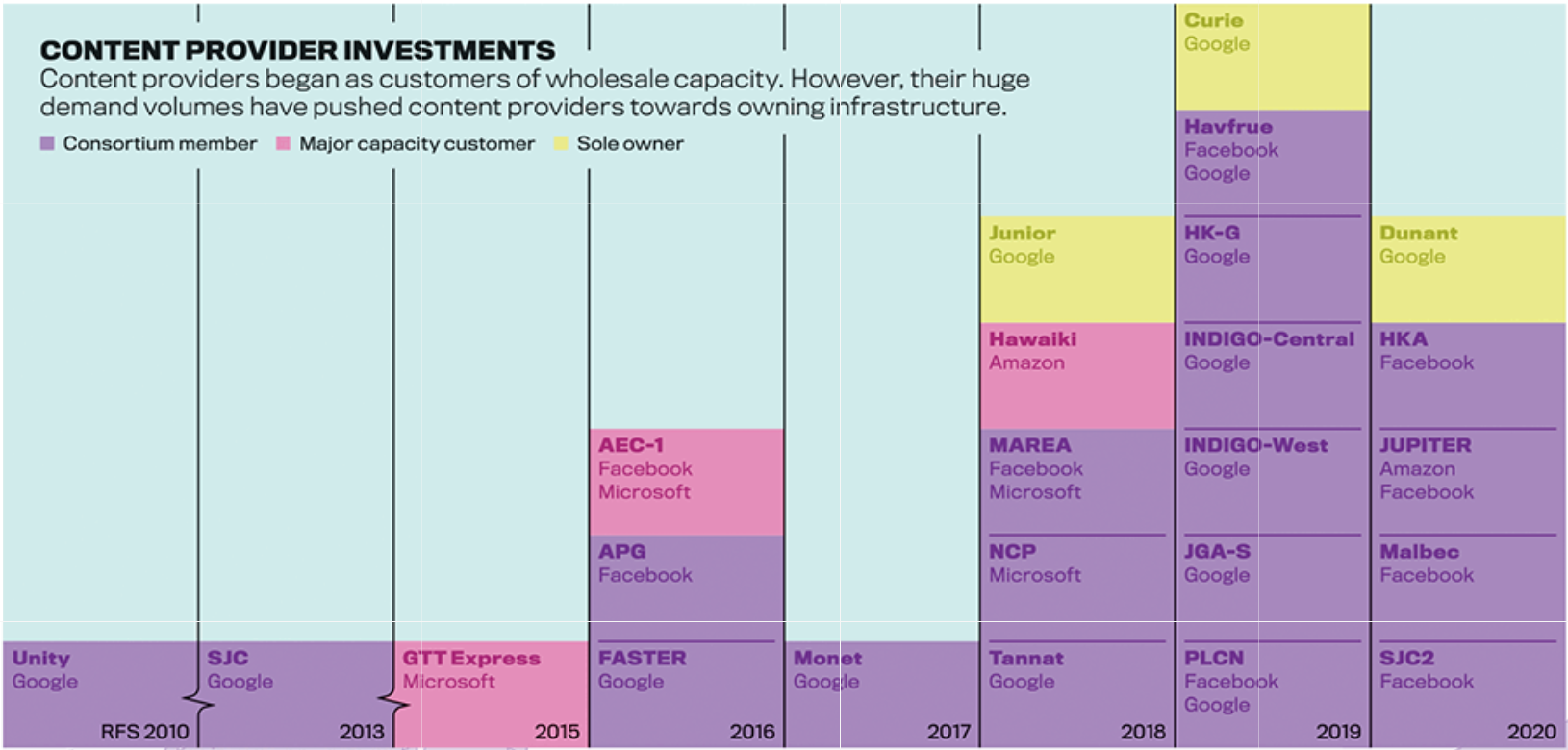

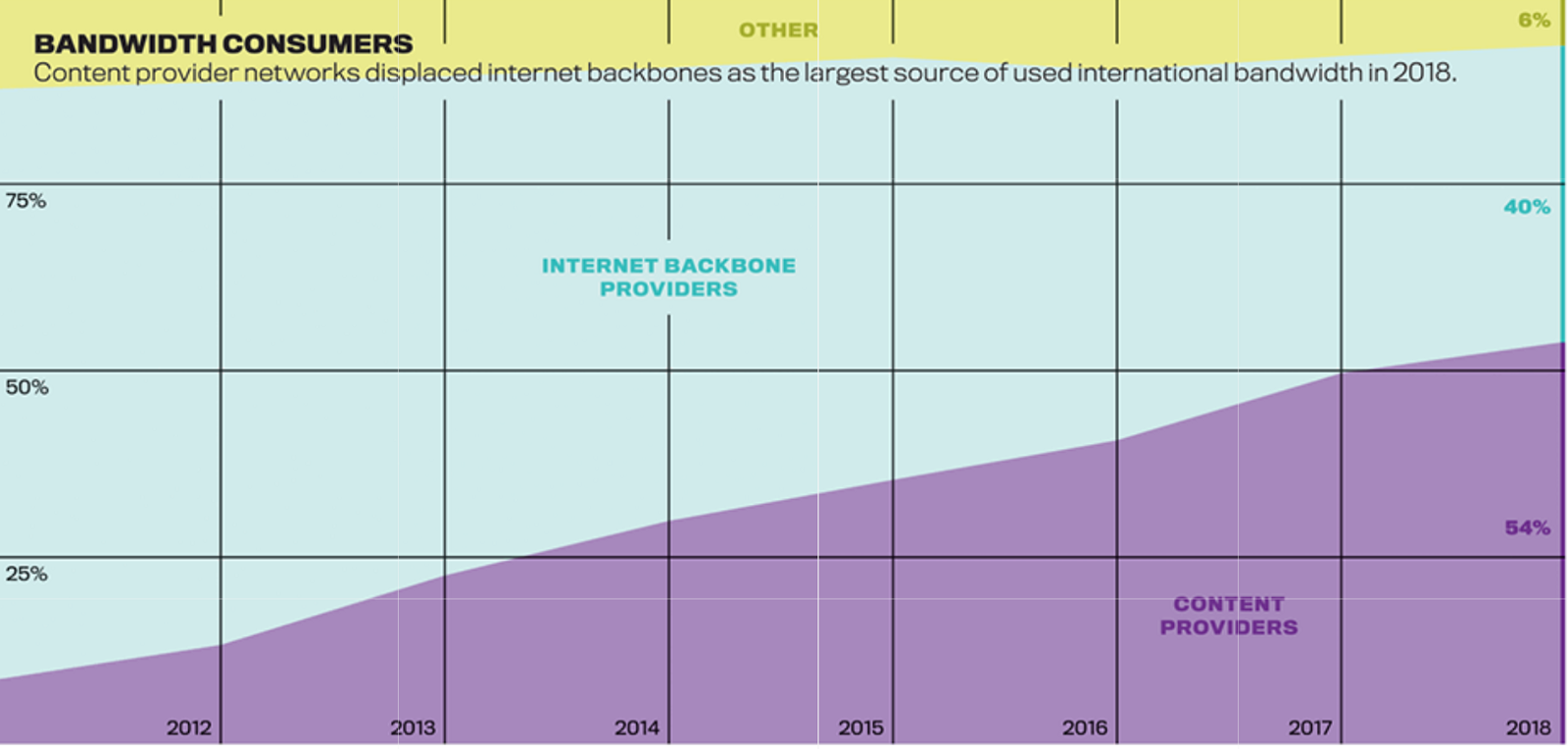

An interesting trend is increased investment by content providers in new cables. Previously Internet backbone providers were the major investors and bandwidth consumers of Internet cable. In the last five years, the cables that are partly owned by Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon has risen eight-fold, and there are more such cables in the pipeline. These content providers also consume over 50% of all international bandwidth and TeleGeography projects that by 2027 they could consumer over 80%.

Figure 2 — Content provider investments (TeleGeography 2019).

Figure 3 — Bandwidth consumers (TeleGeography 2019).

The content providers are currently only deploying their cables on major routes, mostly trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific, to link data centres. Thus, their effect on other routes is less pronounced. But routes like India-Singapore and Europe-Africa are not far in the pipeline. When these few content providers fully expand and dominate the undersea cable network, there could be major ramifications.

Think of the undersea cable network as the new economic trade routes and the commodity in transit as data — arguably the most important commodity of the Information Age. Amazon, Microsoft and Google own close to 65% market share in cloud data storage. This makes them major exporters and importers of data. Imagine them forming an oligopoly to own the routes used to transfer any data. Of course, end consumers would benefit from reduced prices that are passed on by the content providers, who now enjoy large economies of scale from owning cables. But smaller companies looking to compete will be at a disadvantage. They, or anyone else looking to use these cables, could be charged a higher price for bandwidth. This is no different from an oil cartel in some aspects. A worse, but less likely, privacy related concern is if Facebook decides to use all data passing through their cable to ‘improve their services’, regardless of who owns the data.

Don’t worry though — we are nowhere near such a scenario. Yet. Content providers are currently only part owners of cables and Internet backbone providers still have a dominant presence. But if these content providers do decide to own and regulate all cables, which they are capable of, this could very well be the future in store. The companies in question here are already more powerful than most people realize. If you need more convincing, read this article on how difficult life is without them or better yet, listen to this podcast discussing surveillance capitalism.

Experts on antitrust argue that in the age of big tech, consumer welfare should not be the only factor taken into consideration while identifying antitrust behaviour. They suggest that any company stifling competition or making a ‘transaction motivated at the time by avoidance of competition is a good candidate for divestiture after the fact.’ Does the foray by these content providers into undersea cables classify as antitrust behaviour and should there be regulations to prevent this from happening?

The words of Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, ring true today and could become truer tomorrow:

“It’s almost like we woke up and suddenly the Internet was owned and operated by private capital under a kind of regime, a new economic logic that really was not well understood.”

This post originally appeared on Noteworthy – The Journal Blog.

Sarvesh Mathi is a NYU Economics graduate, freelance writing on technology, business and politics.

The views expressed by the authors of this blog are their own

and do not necessarily reflect the views of APNIC. Please note a Code of Conduct applies to this blog.