With the Artemis mission scheduled to put boots on lunar regolith as soon as 2024, NASA has a lot of launching to do — and you can be sure none of those launches will go to waste. The agency just announced 12 new science and technology projects to send to the Moon’s surface, including a new rover.

The 12 projects are being sent up as part of the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, which is — as NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has emphasized strongly — part of an intentional increase in reliance on private companies. If a company already has a component or rover or craft ready to go and meeting a program’s requirements, why should NASA build it from scratch at great cost?

In this case the selected projects cover a wide range of origins and intentions. Some are repurposed or spare parts from other missions, like the Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment. LuSEE is related to the Park Solar Probe’s STEREO/Waves instrument and pieces from MAVEN, re-engineered to make observations and measurements on the moon.

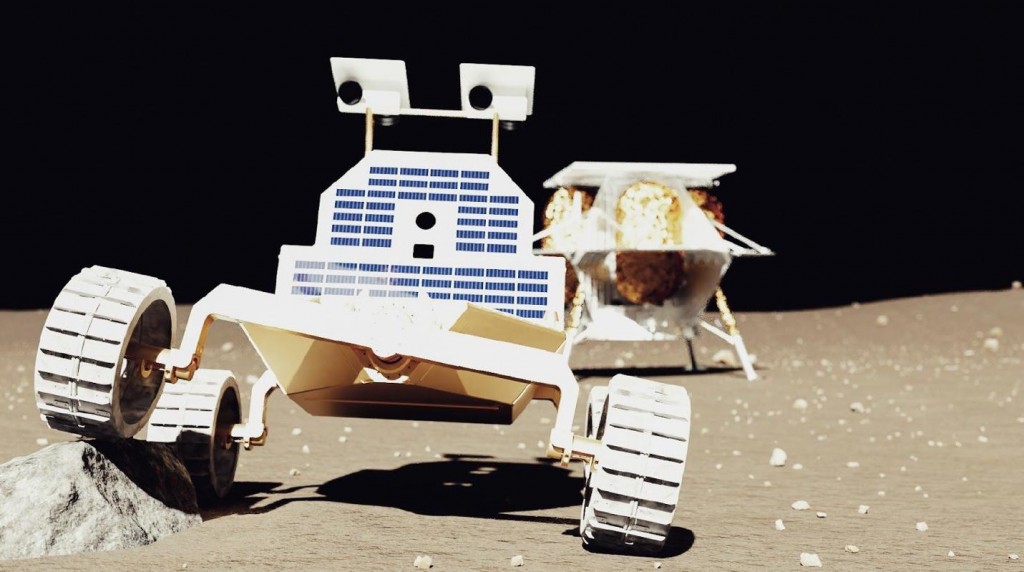

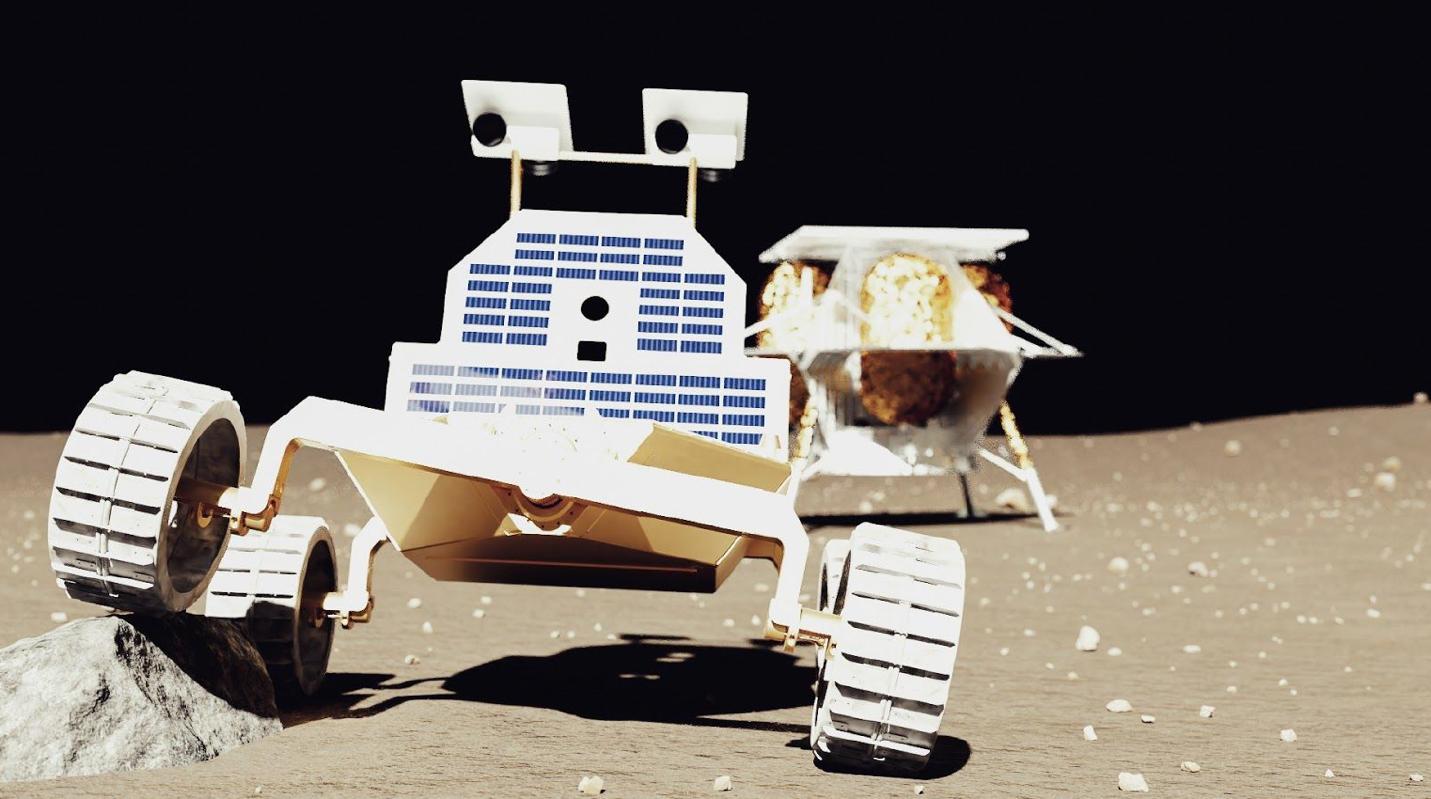

The new funding from NASA amounts to $5.6M, which isn’t a lot to develop a lunar rover from scratch — no doubt it’s using its own funds and working with its partner, Carnegie Mellon University, to make sure the rover isn’t a bargain bin device. With veteran rover engineer Red Whittaker on board, it should be a good one.

“MoonRanger offers a means to accomplish far-ranging science of significance, and will exhibit an enabling capability on missions to the Moon for NASA and the commercial sector. The autonomy techniques demonstrated by MoonRanger will enable new kinds exploration missions that will ultimately herald in a new era on the Moon,” said Whittaker in an Astrobotic news release.

The distance to the lunar surface isn’t so far that controlling a rover directly from the surface is nearly impossible, like on Mars, but if it can go from here to there without someone in Houston twiddling a joystick, why shouldn’t it?

To be clear, this is different from the upcoming CubeRover project and others that are floating around in Astrobotic and Whittaker’s figurative orbits.

“MoonRanger is a 13 kg microwave sized rover with advanced autonomous capabilities,” Astrobotic’s Mike Provenzano told me. “The CubeRover is a 2 kg shoebox sized rover developed for light payloads and geared for affordable science and exploration activities.”

While both have flight contracts, CubeRover is scheduled to go up on the first Peregrine mission in 2021, while MoonRanger is TBD.

Another NASA selection is the Planetary Science Institute’s Heimdall, a new camera system that will point downward during the lander’s descent and collect super-high-resolution imagery of the regolith before, during, and after landing.

“The camera system will return the highest resolution images of the undisturbed lunar surface yet obtained, which is important for understanding regolith properties. We will be able to essentially video the landing in high resolution for the first time, so we can understand how the plume behaves – how far it spreads, how long particles are lofted. This information is crucial for the safety of future landings,” said the project’s R. Aileen Yingst in a PSI release.

The regolith is naturally the subject of much curiosity, since if we’re to establish a semi-permanent presence on the Moon we’ll have to deal with it one way or another. So Projects like Honeybee’s PlanetVac, which can suck up and test materials right at landing, or the Regolith Adherence Characterization, which will see how the stuff sticks to various materials, will be invaluable.

RadSat-G deployed from the ISS for its year-long mission to test radiation tolerance on its computer systems.

Several projects are continuations of existing projects that are great fits for lunar missions. For example, the lunar surface is constantly being bombarded with all kinds of radiation, since the Moon lacks any kind of atmosphere. That’s not a problem for machinery like wheels or even solar cells, but for computers radiation can be highly destructive. So Brock LaMere’s work in radiation-tolerant computers will be highly relevant to landers, rovers, and payloads.

LaMere’s work has already been tested in space via the Nanoracks facility aboard the International Space Station, and the new NASA funding will allow it to be tested on the lunar surface. If we’re going to be sending computers up there that people’s lives will depend on, we better be completely sure they aren’t going to crash because of a random EM flux.

The rest of the projects are characterized here, with varying degrees of detail. No doubt we’ll learn more soon as the funding disbursed by NASA over the next year or so helps flesh them out.