If you’re driving your car from Portland to Merced, you probably rely on GPS to see where you are. But what if you’re driving your Moon rover from Oceanus Procellarum to the Sea of Tranquility? Actually, GPS should be fine — if this NASA research pans out.

Knowing exactly where you are in space, relative to other bodies anyway, is definitely a non-trivial problem. Fortunately the stars are fixed and by triangulating with them and other known landmarks, a spacecraft can figure out its location quite precisely.

But that’s so much work! Here on Earth we gave that up years ago, and now rely (perhaps too much) on GPS to tell us where we are to within a few meters.

By creating our own fixed stars — satellites in geosynchronous orbits — constantly emitting known signals, we made it possible for our devices to quickly sample those signals and immediately locate themselves.

That sure would be handy on the Moon, but a quarter of a million miles makes a lot of difference to a system that relies on ultra-precise timing and signal measurement. Yet there’s nothing theoretically barring GPS signals from being measured out there — and in fact, NASA has already done it at nearly half that distance with the MMS mission a few years ago.

“NASA has been pushing high-altitude GPS technology for years,” said MMS system architect Luke Winternitz in a NASA news release. “GPS around the Moon is the next frontier.”

Astronauts can’t just take their phones up there, of course. Our devices are calibrated for catching and calculating signals from satellites known to be in orbit above us and within a certain range of distances. The time for the signal to reach us from orbit is a fraction of a second, while on or near the Moon it would take perhaps a full second and a half. That may not sound like much, but it fundamentally affects how the receiving and processing systems have to be built.

The idea is to use GPS instead of relying on NASA’s network of ground and satellite measurement systems, which must exchange data to the spacecraft and eat up valuable bandwidth and power. Freeing up those systems could empower them to work on other missions and let more of the GPS-capable satellite’s communications be dedicated to science and other high-priority transmissions.

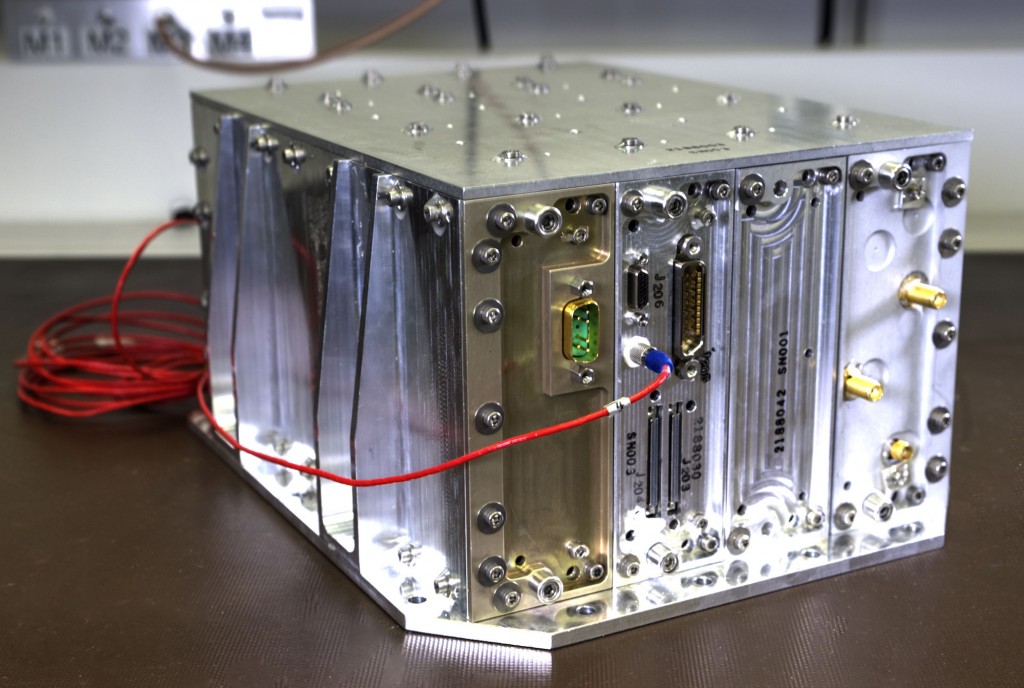

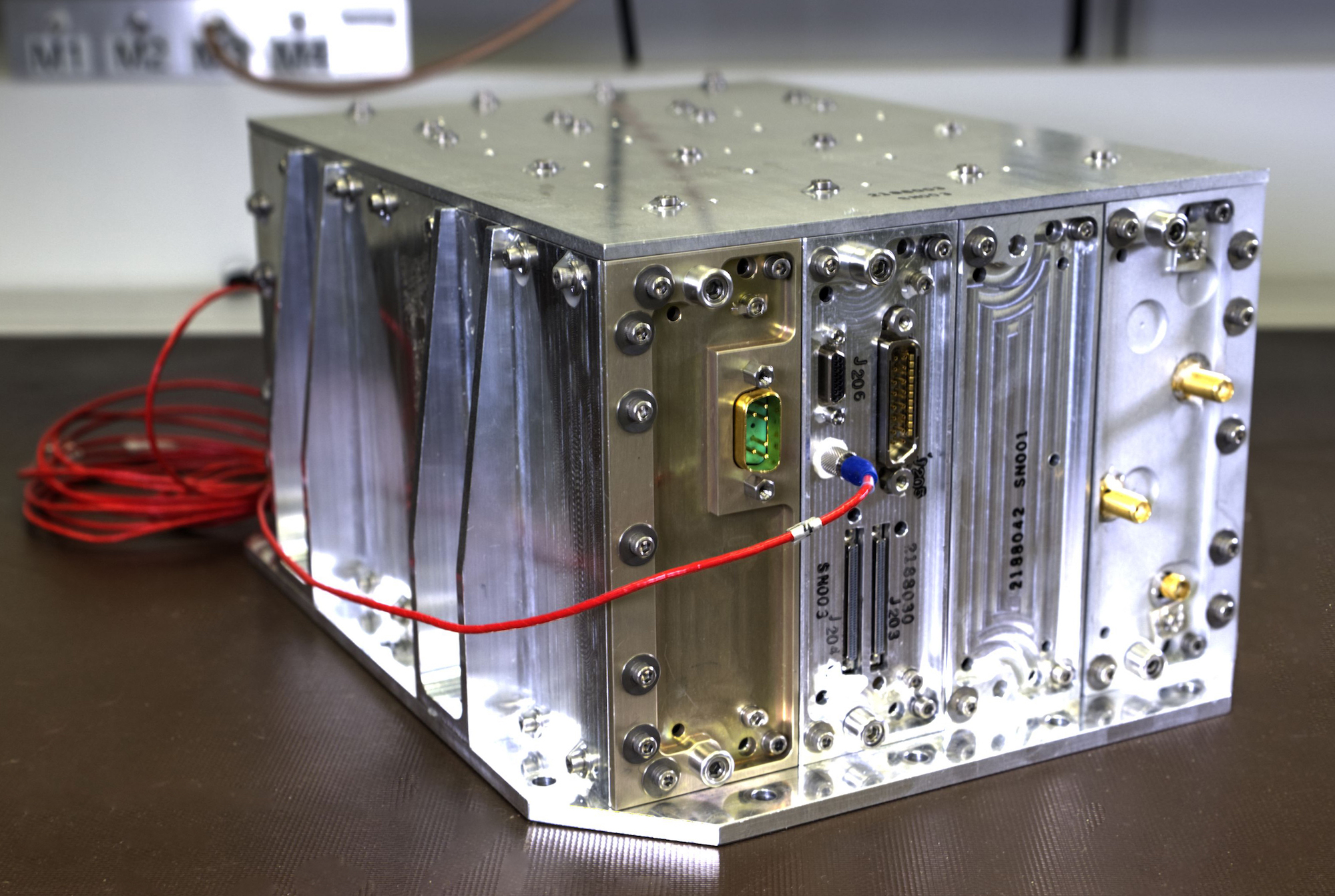

The team hopes to complete the lunar NavCube hardware by the end of the year and then find a flight to the Moon on which to test it as soon as possible. Fortunately, with Artemis gaining traction, it looks as if there will be no shortage of those.