Few traffic jams are as organized and coordinated as the ones that took place nationwide in the morning of September 3, 1967, on the streets of Sweden. That day, at exactly five in the morning, all traffic came to a standstill. Then slowly and cautiously, motorists and cyclists steered their cars, bikes and cycles across the road to the other side. Sweden had decided that they are no longer going to drive on the left side of the road.

Chaos unfolded across the country as million of motorists, who had been driving on the “wrong” side of the road all their lives, adjusted to the new rules. Daily commutes became profoundly unfamiliar. The hardest part was unlearning many of the things they had committed to muscle memory, which constitutes much of driving itself.

No wonder, the Swedish protested when a suggestion was put forward in the early 1950s. When a referendum was held in 1955, 83 percent voters voted against the idea. Despite this, the government pushed forward for the change to put Sweden on the same path as the rest of its European neighbors.

The majority of the world drive on the right side of the road, although in the past the Romans and the Greeks, and thus most of Europe, marched or rode on the left. This allowed horsemen to hold the reins with their left hand and swords with their right hand to deal with highwaymen. The shift from left to right took place in the United States, when teamsters started using large freight wagons pulled by several pairs of horses. The wagons had no driver’s seat, so the driver sat on the left rear horse and held his whip in his right hand allowing him to control all the horses. Seated on the left, the driver naturally preferred that other wagons pass him on the left so that he could be sure to keep clear of the wheels of oncoming wagons. He did that by driving on the right side of the road. The British kept to the left because they had smaller wagons and had no difficulties continuing with the tradition. Countries that became part of the British Empire adopted the left-hand rule. Some countries eventually changed to the right, such as Canada, to make border crossings to and from the United States easier.

Sweden had similar reasons—all of Sweden’s neighbors, including Norway and Finland with which Sweden shares land borders, drove on the right. The most pressing issue, however, was rode safety. Despite driving on the left, as many as ninety percent of cars on the rode had steering wheels on the left side of the vehicle, because the majority of these were imported from the United States. Curiously, many Swedish car manufacturers themselves, such as Volvo, produced cars that were meant to drive on the right side of the rode even for the domestic market. The result was too many road accidents.

In 1963, the Swedish government ruled that the country would switch to right hand traffic. September 3, 1967, was set as the day the changeover would take place. That day would be known as Dagen H or H-Day, short for “Högertrafikomläggningen”, which means “right-hand traffic diversion”.

Preparing the country and its nearly 8 million residents for the massive changeover was a costly and complicated endeavor. Traffic lights had to reversed, road signs changed, intersections redesigned, lines on the road repainted, buses modified to provide doors on both sides, and bus stops relocated. Many of these modifications were started months in advance and completed just before H-Day. New traffic signals were kept wrapped in black plastic until the final hours. Similarly, new lines painted on the roads were covered with black tape. Around 360,000 street signs across the country were switched largely on a single day.

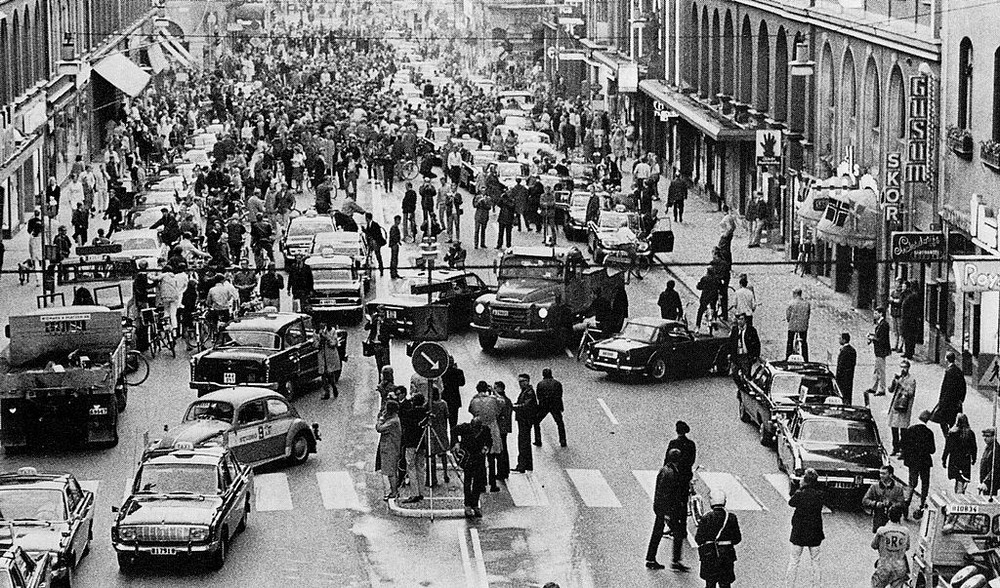

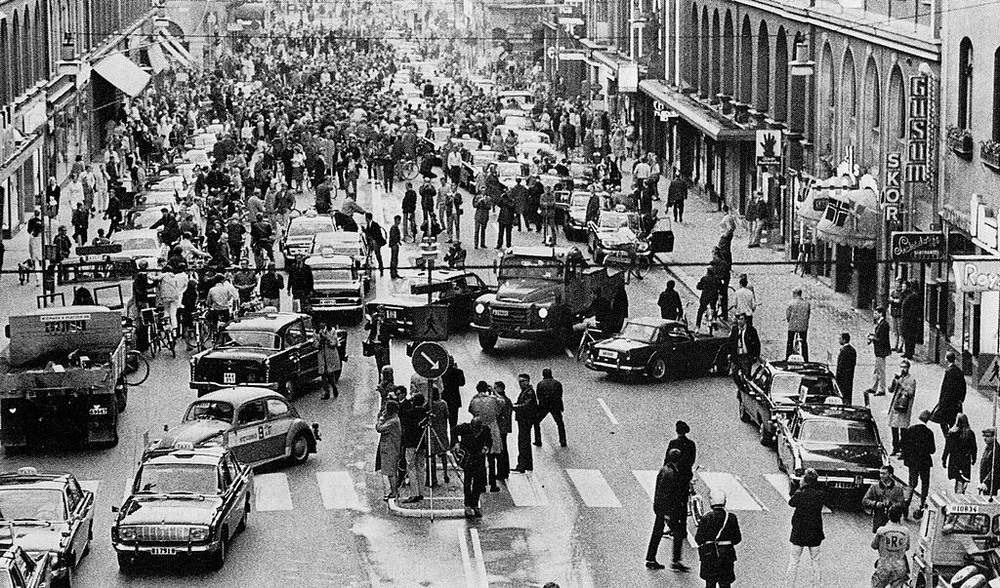

In the hours leading up to the changeover, there was almost a festive atmosphere. Crowds started gathering in the early morning light. There were fireworks and singing. Most cars were kept off the road to allow the construction workers to work. At 4:50 AM, a horn blared and a loudspeaker announced, “Now is the time to changeover!”. The new road signs were revealed, and the cars re-routed to the opposite side.

Thanks to the careful planning, the mammoth changeover went beautifully. Aside from the inevitable traffic jams and a few minor accidents, nobody died. The scores of journalists who had gathered on the streets expecting a bloodbath were almost disappointed.

In the weeks and months immediately following the change, traffic accidents fell dramatically due to the extra caution people drove with because of the jarring reversal in traffic. Of course, once people got used to it, about three years later, accident and fatality rates returned to their original levels.

Overall, the project cost the Swedish tax payers 628 million kronor, equivalent to around 2.6 billion kronor ($316 million) in today’s money. But compared to the scale of the project, this figure was actually relatively small, says economic historian Lars Magnusson.

A thing like Dagen H would have been nearly impossible to execute in current times, feels Peter Kronborg, author of Håll dig till höger Svensson—a book about Dagen H. The Swedish public would be outraged if politicians went ahead with a project so vehemently opposed in a referendum. The media was also less critical at that time, and only reported what the experts told them. “If the experts said that this would not be very costly and it would benefit everybody, well, the media would accept that and I suppose the public would accept it as well,” chips in Lars Magnusson.

At the time of Dagen H there was only one television channel and one radio channel and “everybody watched and listened to them”. But with today’s diversity of media channels including the social media, reaching the entire population would be a much more complicated matter.

The Swedish road network is also more developed than it was fifty years ago, and there are many times more cars on the road that would increase the financial cost by a factor of ten, at least. Sweden’s current transportation strategists believe that an equivalent to Dagen H could not be implemented anywhere near as smoothly today as it was in 1967.

In 1997, Sweden launched another traffic initiative called Vision Zero that aimed to eliminate all traffic fatalities and severe injuries especially on the highways. Since then the country has changed its focus from speed and convenience to safety when building roads. Low urban speed-limits, pedestrian zones and barriers that separate cars from bikes and oncoming traffic have lowered road deaths. Sweden also pioneered the 2+1 system of road where a two-way lane becomes three-way every few hundred meters to allow fast moving cars to safely overtake slow moving traffic. These roads are now implemented in much of Europe and also in some places in Canada and Australia. Today Sweden has one of the world’s lowest road death rates—270 deaths in 2016, compared to 1,313 in 1966, the year before Dagen H.