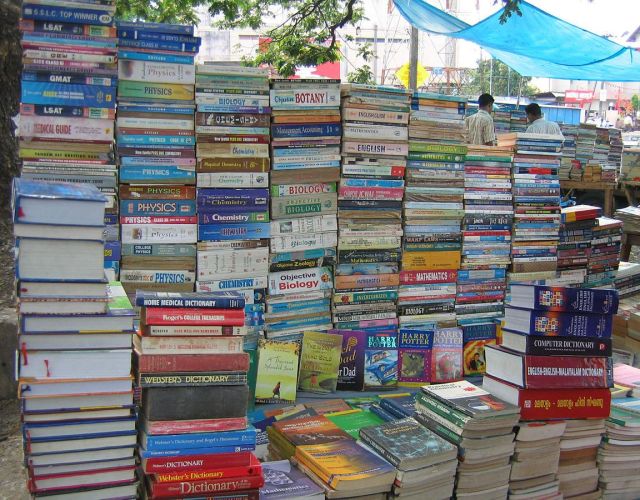

Secondhand Bookstore, Kannur, Kerala. Image by Vinayaraj. CC BY-SA 3.0

Adam Minter is a writer for Bloomberg View and a wide range of other publications. He is also author of Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade. His forthcoming book, Secondhand, is due out later this year and covers the global trade in secondhand commodities. Here is Adam’s interview with Discard Studies:

DS: What are the main myths you have to de-mythologize every time you address discards?

AM: There’s really only one: the persistent idea that developed countries “dump” their recyclable and re-usable discards on developing countries.

It’s a difficult myth to address for three key reasons.

First, it builds upon decades of reporting and research on the ways that developed country companies and governments externalize pollution. In newsrooms, and with news consumers, that body of knowledge creates a near automatic presumption of “externalization” when presenting narratives about the transnational trade in discards – even if there might be another, more accurate interpretation. Journalists are sensitive to that presumption.

Second, it’s a narrative that’s seductively easy to repeat (or, less charitably, copy). All you need is a map with a red line showing the route a device took from a rich place to a poor one. Recently, a common narrative device in many stories about e-waste dumping is the GPS tracker hidden in a shipping container or device that pings the journey from rich world to developing world. Many if not most non-specialists will naturally assume that the purpose of the journey is to save on the costs of “proper” recycling in the rich country. Throw in visuals of discards on fire, or in other states of disassembly that are unsafe, and the story more or less, writes and edits itself.

Third, and perhaps most important, mainstream media tends to view discards solely through an environmental lens. That’s understandable but insufficient if the goal is to understand why discards are traded and move around the globe.

For that, you need a commercial lens. Let me use an example that’s currently in the news: the shift of plastic scrap imports from China, which has effectively banned much of the trade, to Malaysia. In the wake of that shift, there have been dozens of reports – everyone from the BBC to Malaysian local media – on the “dumping” of foreign [plastic] waste in Malaysia.

Now here’s the problem with the “dumping” narrative. At the moment, the cost of sending a forty-foot shipping container of discarded plastics from the Port of Los Angeles to Port Klang, Malaysia (where many of California’s plastic exports are heading since China’s restrictions on imports), is roughly $1,200. Meanwhile, the cost of “tipping” a ton of solid waste into a L.A.-area landfill is around $52 per ton. That’s a problematic pair of numbers if you’re committed to explaining waste exports as externalization. After all, if it’s cheaper to “dump” in Los Angeles, than to “dump” in Malaysia – why are plastic recyclers in Los Angeles “dumping” in Port Klang?

The answer should be obvious: the plastics aren’t being dumped, they’re being purchased by someone in Malaysia (who, like an Amazon customer, also pays the freight). And the reason they’re willing to put up that money is because the plastic has value as a raw material for manufacturing or re-use. Invoices, shipping manifests, and customs assessments are the obtainable documentary evidence for these transactions (likewise, shipping and tipping rates are easily google-able).

Recovered plastics being readied for shipping. Image by Max Liboiron.

This isn’t a state of economic affairs unique to Malaysia. In the two decades I’ve covered the transglobal trade in discards, I’ve yet to see a shipping container of discards “dumped” on a developing country. In every case, the material in the containers was purchased and imported for more than what it would cost to “dump” at home. Of course, the discards weren’t always processed or used in a way that conforms to health, safety, and environmental standards found in many developed countries. But it’s difficult to argue that somebody is dumping something on a poor country when a person in the poor country is paying for the stuff.

One last thing. Consciously or unconsciously, when reporters, academics, and news consumers use the term “dumping” they implicitly deny agency to the highly sophisticated trading and processing businesses that operate across the developing world. If there is one underlying theme in my work on discards over the years it is this: the millions of people who work on discards in the developing world have agency. Continued use of the term “dumping” denies it to them.

DS: Your previous book, Junkyard Planet, was about the global industrial trade in scrap (or recyclables) and your upcoming book is about globalized trails of secondhand commodities – everything from clothes to collectables. What draws you to topics like these? What about their lives as discarded things (or commodities) makes them good for telling stories for understanding global trade that other things (or commodities) might be less good at?

AM: As a journalist, I’m interested in stories that question conventional narratives, especially if those narratives are used to advance moral judgements. Early in my career I sought out profiles of politicians with whom I disagreed and – once I moved to China – Catholic churches licensed by the Catholic Patriotic Association (for the record: I’m Jewish). In most cases, I found nuance and complexity.

Discards, and particularly the globalization of discards, is a similar kind of story. When I moved to China in 2002, the moral consensus on the globalized trade had already hardened into something like the dumping narrative. My instinct was that nothing is so simple, that there had to be something more to the story.

Full disclosure: that instinct is an inherited trait. For years my father owned a Minneapolis scrap yard where I worked as a child and teenager, often doing manual labor (like hand-sorting plumbing scrap). Even though I chose not to go into the business, I continue to feel a strong kinship with the smalltime traders, peddlers, and entrepreneurs who work in it, especially in developing countries. I also feel a responsibility to share a more “dimensional” view of their lives than what they get from narratives depicting them as exploited or dumped upon.

Nonetheless, I spent twelve years covering China’s recycling industry, but it was only in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis that I came to appreciate that I was following a story bigger than scrap. What happened then was shocking: as global consumer demand crashed, Chinese factories stopped buying recyclables (and other raw materials), forcing some cities in developed countries to landfill their scrap paper. During this period, I agreed to appear on an Irish radio show to help explain why local recyclers were sending scrap cardboard to the dump. To my surprise, I was the unlucky recipient of 30 minutes of abuse from people calling into the show to complain about how important their recyclables were to them, and how unhappy they were that their local governments (and, by extension, China), didn’t share their views!

From that point, I slowly began to understand that people in consumption-based societies assemble their identities via stuff, and become very emotional when those identities – and that stuff- is discarded in ways that don’t match their values. Over the years I’ve come to the conclusion that consumers actually care more about how their stuff is discarded, than how it is manufactured.

In any case, Junkyard Planet addressed industrial recycling, primarily; the new book, Secondhand, deals with the journey of personal property, and I’m hopeful that it will spur readers to think more seriously about the relationship between consumption and the sustainability of globalization. I can’t think of a better way to address the subject.

DS: People seem to be very emotionally attached to how their discards are handled compared to how their stuff is manufactured. This is especially interesting given how much work there is done by activists, academics, and journalists on labour conditions in manufacturing—everything from Marx to Upton Sinclair to much more contemporary campaigns like iSlave or Fashion Revolution. What do you think accounts for the differences in emotional reactions to discarding compared to manufacturing?

AM: I think it’s the rare consumer in 2019 who isn’t at least tangentially aware of the social and environmental consequences of manufacturing. And it’s even rarer to find a consumer who’s capable of avoiding the moral (and financial) compromises necessary to live up to the values that academics, activists and journalists often ask consumers to embrace (or, minimally, reflect upon). For example, if you want to decarbonize transport by purchasing an electric car, you implicitly accept the often troubling ways that cobalt is mined for electric car batteries. Lots of people – probably most people – make that sort of compromise on a daily basis, whether it’s at the supermarket buying vegetables, or at the GAP buying an affordable sweater. As a result, I think there’s a limit to how much outrage an activist can generate over how stuff is manufactured. Everyone is already compromised, and you can only push people so far in terms of guilt before they shut down.

Discards occupy an entirely different emotional ecosystem, especially in developed countries where objects are donated and dropped-off, rather than sold. When a consumer donates something, or drops it into a blue bin, they typically have a reasonable expectation that the objects will be re-used or repurposed in a way conforming to their values – and they have some agency in the decision (there are many charities). When you combine that expectation with the powerful identity associations attached to personal property, the outcomes can be explosive — especially when donated and dropped-off objects are handled in ways that don’t meet the donor’s expectations.

I didn’t really appreciate that emotional landscape until I started spending time with people and companies in the US who help senior citizens “downsize” their property before a move to smaller quarters, typically a senior living facility. And what I saw during downsizing cleanouts is a lot of resistance to discarding by the very people who paid (handsomely, in most cases) to have someone come and help them discard. Before the owners would let go, they needed reassurance that the stuff will be valued and reused in ways that conform to their values.

An example of how this works is given in the following short, modified passage from Secondhand. In it, I interview a well-paid property sorter in Minnesota. For background: her client base tends to be relatively affluent Americans in their 70s and older:

“There’s a grieving process,” she says. “When you got that wedding china, you were going to keep it forever. I have clients break down.”

The process is made even more difficult by changing tastes. The fine china and antiques appreciated by Americans born in the middle of the twentieth century aren’t in much demand from the younger generations. “People just don’t want it. But seniors want people to want it,” she says. “‘Oh, my kids will take it.’ No, they won’t.”

In the course of sorting someone’s stuff, her best tactic is to persuade the clients that stuff won’t be wasted. “Men won’t get rid of tools. Women, Tupperware. So we tell them the Tupperware can be recycled. The tools can be used by someone else.” Then it’s left to the senior move manager to figure out what to do with what’s left behind, and quickly.

It’s a fairly simple lesson: don’t arrive at someone’s house with the intention of tossing stuff into the garbage. But how that lesson plays out in the course of a home cleanout tells me a great deal about how a certain demographic at least – affluent, elderly Americans – view their discards.

DS: Not to give away any spoilers from your upcoming book, but is there a particular piece of stuff (or maybe a category of stuff) where identity, emotion, and discarding seem to get especially charged? Do you see variations from place to place in those patterns linking stuff, identity, and emotion?

AM: Let me start by answering the second question, first. The early chapters of Secondhand are largely focused on the generation of discards, especially via home cleanout businesses. Some are in the United States, and some are in Japan, where there’s thriving industry devoted to cleaning out homes left behind by the country’s growing numbers of elderly with no heirs.

I purposely contrast the cleanout industries in the two countries, and highlight some of the difference. I think the most important is that – barring a few exceptions, especially at the high end of the market – consumers in North America and Europe are committed to a donation model for discarding clothing and durable goods, and consumers in Japan – as in most parts of the world – tend to sell them. My sense is that consumers become less exercised over the moral dimensions of what ultimately happens to discards when they dispose of them via commercial transactions. After all, nobody pays for something in order to trash it. They pay to get some value – re-usable, extractable, whatever – from it. For the seller, that allows for a clean(er) break.

And I think that’s a key reason why we don’t see much activism against the export of discards from Japan and other developed (and developing) Asian nations: the commercial transactions resolve many of the moral quandries and questions that individual consumers might have with disposaing of their discards. Of course, there are other reasons, too. For example, even the most developed countries in Asia are home to living memories of poverty and development and reliance upon secondhand goods imported from wealthier regions. So, naturally, they’ll be more accepting of the trade.

Regarding your first question – I don’t think anyone will be surprised to learn that fashion and apparel discards are highly charged. Who doesn’t have a favorite shirt, sweater, or other garment associated with life events? And who doesn’t want to see that garment re-used and loved? Combine that emotion with the standard narrative of “dumping” and the outcome is predictably emotional.

I think that narrative is going to change in the next decade, thanks to two factors. First, the global market for new apparel is growing fast, especially in developing Asia. As a result, there’s a growing glut of secondhand clothes, globally, and diminishing number of consumers who will want them. Second, the technology of textile recycling is developing quickly. I don’t want to be a technology prognosticator, but I think in the next decade or so we’ll see chemical recycling of textiles. In effect, our old garments can be dumped in a vat, dissolved, and transformed into new threads. This is pure speculation on my part, but I think many consumers will recoil at seeing their garments re-used in such a way. I don’t dive into this question in Secondhand, but I do think it’ll be fascinating to see how these twin phenomena play out.