Group f/64 was a group founded by seven 20th-century San Francisco Bay Area photographers who shared a common photographic style characterized by sharply focused and carefully framed images seen through a particularly Western (U.S.) viewpoint. In part, they formed in opposition to the pictorialist photographic style that had dominated much of the early 20th century, but moreover, they wanted to promote a new modernist aesthetic that was based on precisely exposed images of natural forms and found objects.[1]

Background[edit]

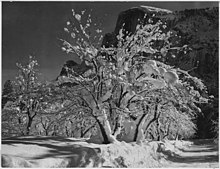

The late 1920s and early 1930s were a time of substantial social and economic unrest in the United States.[2] The United States was suffering through the Great Depression, and people were seeking some respite from their everyday hardships. The American West was seen as the base for future economic recovery because of massive public works projects like the Hoover Dam.[3] The public sought out news and images of the West because it represented a land of hope in an otherwise bleak time. They were increasingly attracted to the work of such photographers as Ansel Adams, whose strikingly detailed photographs of the American West were seen as “pictorial testimony…of inspiration and redemptive power.”[1]

At the same time, workers throughout the country were beginning to organize for better wages and working conditions. There was a growing movement among the economically oppressed to band together for solidarity and bargaining strength, and photographers were directly participating in these activities. Shortly before Group f/64 was formed, Edward Weston went to a meeting of the John Reed Club, which was founded to support Marxist artists and writers.[4] These circumstances not only helped set up the situation in which a group of like-minded friends decided to come together around a common interest, but they played a significant role in how they thought about their effort. Group f/64 was more than a club of artists; they described themselves as engaged in a battle against a “tide of oppressive pictorialism” and purposely called their defining proclamation a manifesto, with all the political overtones that the name implies.[4]

While all of this social change was going on, photographers were struggling to redefine what their medium looked like and what it was supposed to represent. Until the 1920s the primary aesthetic standard of photography was pictorialism, championed by Alfred Stieglitz and others as the highest form of photographic art. That began to change in the early 1920s with a new generation of photographers like Paul Strand and Imogen Cunningham, but by the end of that decade there was no clear successor to pictorialism as a common visual art form. Photographers like Weston were tired of the old way of seeing and were eager to promote their new vision.

Imogen Cunningham: a botanical photograph of a succulent plant by Imogen Cunningham, 1920. This image is thought to have been in the first Group

f/64 exhibit in 1932.

Formation and participants[edit]

Group f/64 was created when photographers Willard Van Dyke and Ansel Adams decided to organize some of their fellow photographers for the purposes of promoting a common aesthetic principle. Van Dyke was an apprentice to Edward Weston, and in the early 1930s he established a small photography gallery in his home at 683 Brockhurst in Oakland. He called the gallery 683 “as our way of thumbing our nose at the New York people who didn’t know us”,[5] a direct reference to Stieglitz and his earlier New York gallery called 291. Van Dyke’s home/gallery became a gathering place for a close circle of photographers that eventually became the core of Group f/64.

In 1931, Weston was given an exhibition at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, and because of the public’s interest in that show the photographers who gathered at Van Dyke’s home decided to put together a group exhibition of their work. They convinced the director at the de Young Museum to give them the space, and on November 15, 1932, the first exhibition of Group f/64 opened to large crowds.[6]

A small poster at the exhibition said:

Group f/64 —

announces an exhibition of photographs at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum.

From time to time various other photographers will be asked to display their work with Group f/64. Those invited for the first showing are:

This first exhibition consisted of 80 photographs, including 10 by Adams, 9 each by Cunningham, Edwards, Noskowiak, Swift, Van Dyke and Edward Weston, and 4 each by Holder, Kanaga, Lavenson and Brett Weston. Edward Weston’s prints were priced at $15 each; all of the others were $10 each. The show ran for six weeks.[6]

In 1934 the group posted a notice in Camera Craft magazine that said “The F:64 group includes in its membership such well known names as Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke, John Paul Edwards, Imogene [sic] Cunningham, Consuela [sic] Kanaga and several others.”[6] While this announcement implies that all of the photographers in the first exhibition were “members” of Group f/64, not all of the individuals considered themselves as such. In an interview later in her life, Kanaga said “I was in that f/64 show with Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke and Ansel Adams, but I wasn’t in a group, nor did I belong to anything ever. I wasn’t a belonger.”[7]

Some photo historians view Group f/64 as an organized faction consisting of the first seven photographers, and view the other four photographers as associated with the group by virtue of their visual aesthetics.[6] However, in an interview in 1997[8] Dody Weston Thompson reported that in 1949 she was invited to join Group f/64. She also recounted that her husband Brett Weston, whom she married in 1952, also considered himself a member. This suggests that an absolute delineation of membership in historical terms is difficult to determine in light of the informality of the group’s shifting social composition during the 1930s and 1940s.

Name and purpose[edit]

There is some difference of opinion about how the group was named. Van Dyke recalled that he first suggested the name “US 256”, which was then the commonly used Uniform System designation for a very small aperture stop on a camera lens. According to Van Dyke, Adams thought the name would be confusing to the public, and Adams suggested “f/64″, which was a corresponding aperture setting for the focal system that was gaining popularity. However, in an interview in 1975 Holder recalled that he and Van Dyke thought up the name during a ferry ride from Oakland to San Francisco.[6] Regardless, the name became the now famous Group f/64.

The term f/64 refers to a small aperture setting on a large format camera, which secures great depth of field, rendering a photograph evenly sharp from foreground to background. Such a small aperture sometimes implies a long exposure and therefore a selection of relatively slow moving or motionless subject matter, such as landscapes and still life, but in the typically bright California light this is less a factor in the subject matter chosen than the sheer size and clumsiness of the cameras, compared to the smaller cameras increasingly used in action and reportage photography in the 1930s.

This corresponds to the ideal of straight photography which the group espoused in response to the pictorialist methods that were still in fashion at the time in California (even though they had long since died away in New York).

Contemporary photographic convention denotes lens apertures with a slash, such as f/22 or f/64, but in its writings the group always used a dot or period instead (as in “f.64″).

Manifesto[edit]

Group f/64 displayed the following manifesto at their 1932 exhibit:

The name of this Group is derived from a diaphragm number of the photographic lens. It signifies to a large extent the qualities of clearness and definition of the photographic image which is an important element in the work of members of this Group.

The chief object of the Group is to present in frequent shows what it considers the best contemporary photography of the West; in addition to the showing of the work of its members, it will include prints from other photographers who evidence tendencies in their work similar to that of the Group.

Group f/64 is not pretending to cover the entire spectrum of photography or to indicate through its selection of members any deprecating opinion of the photographers who are not included in its shows. There are great number of serious workers in photography whose style and technique does not relate to the metier of the Group.

Group f/64 limits its members and invitational names to those workers who are striving to define photography as an art form by simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods. The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography. Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form. The production of the “Pictorialist,” on the other hand, indicates a devotion to principles of art which are directly related to painting and the graphic arts.

The members of Group f/64 believe that photography, as an art form, must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium, and must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself.

The Group will appreciate information regarding any serious work in photography that has escaped its attention, and is favorable towards establishing itself as a Forum of Modern Photography.[6]

Aesthetics[edit]

Photography historian Naomi Rosenblum described Group f/64’s vision as focused on “what surrounded them in such abundance: the landscape, the flourishing organic growth and the still viable rural life. Pointing their lenses at the kind of agrarian objects that had vanished from the artistic consciousness of many eastern urbanites – fence posts, barn roofs, and rusting farm implements – they treated these objects with the same sharp scrutiny as were latches and blast furnaces in the East. However, even in California, these themes look to a vanishing way of life, and the energy contained in the images derived in many instances from formal design rather than from the kind of intense belief in the future that had motivated easterners enamored of machine culture.”[6]

In 1933 Adams wrote the following for Camera Craft magazine:

My conception of Group f/64 is this: it is an organization of serious photographers without formal ritual of procedure, incorporation, or any of the restrictions of artistic secret societies, Salons, clubs or cliques…The Group was formed as an expression of our desire to define the trend of photography as we conceive it…Our motive is not to impose a school with rigid limitations, or to present our work with belligerent scorn of other view-points, but to indicate what we consider to be reasonable statements of straight photography. Our individual tendencies are encouraged; the Group Exhibits suggest distinctive individual view-points, technical and emotional, achieved without departure from the simplest aspects of straight photographic procedure.[6]

History[edit]

After their initial show in 1932, records indicate that some or all of the photographs from that show were exhibited in Los Angeles, Seattle, Portland, Oregon and Carmel. There are no detailed lists of the photos in those shows, so it has been impossible to say exactly which images were exhibited.[6]

By 1934 the effects of the Great Depression were felt throughout California, and the Group members had a series of difficult discussions about the premises for art in those challenging economic times. The effects of the Depression, coupled with the departure of several members of the group from San Francisco (including Weston who moved to Santa Barbara to be with his son and Van Dyke who moved to New York) led to the dissolution of Group f/64 by the end of 1935. Many of its members continued to photograph and are now known as some of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

The most complete collections of prints from Group f/64 photographers are now housed at the Center for Creative Photography and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

- ^ a b Hirsch, Robert (2000). Seizing the Light: A History of Photography. McGraw-Hill. pp. 245–246. ISBN 0-697-14361-9.

- ^ Encarta. “Great Depression in the United States”. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ James Roark; et al. (2007). The American Promise: A Compact History. II (3rd ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s. p. 610. ISBN 0-312-44842-2.

- ^ a b David Peeler (2002). in Original Sources: Art and Archives at the Center for Creative Photography (edited by Amy Rule and Nancy Solomon. Center for Creative Photography. pp. 107–110.

- ^ Morse, Helen (June 1978). “Willard Van Dyke: A Portfolio”. Image. 21 (2): 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Heyman, Therese Thau (1992). Seeing Straight: The f.64 Revolution in Photography. Oakland Museum. pp. 20–24, back cover.

- ^ Margaretta K. Mitchell (1979). Recollections: Ten Women of Photography. NY: Viking Press. pp. 158–160.

- ^ “Exposures: The History of American Landscape Photography”. Youtube.com. 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2013-01-15.